January 18, 2021

January 18, 2021

To state that the enactment of the recent farm laws that seek to reform the existing agricultural framework is mired in controversy, would be a masterly understatement. On one hand, the Indian Government has been accused of bypassing parliamentary procedures and passing the bills unilaterally without the involvement of States or referring the bills to a Standing Committee of Parliament. On the other, opposition parties and farmers are denouncing the new laws as anti-farmer and exploitative. Some are even going so far as to call them “death warrants.”

To fully comprehend the nuances of the three laws, we need to go back at least two decades to the genesis of agricultural reforms in India. The first-ever National Agricultural Policy

(NAP) was announced in the year 2000, as part of a government-proposed concept called the “Rainbow Revolution.” Among various provisions, the NAP envisaged that “private sector participation will be promoted through contract farming and land leasing arrangements to allow accelerated technology transfer, capital inflow and assured market for crop production, especially of oilseeds, cotton and horticultural crops.”

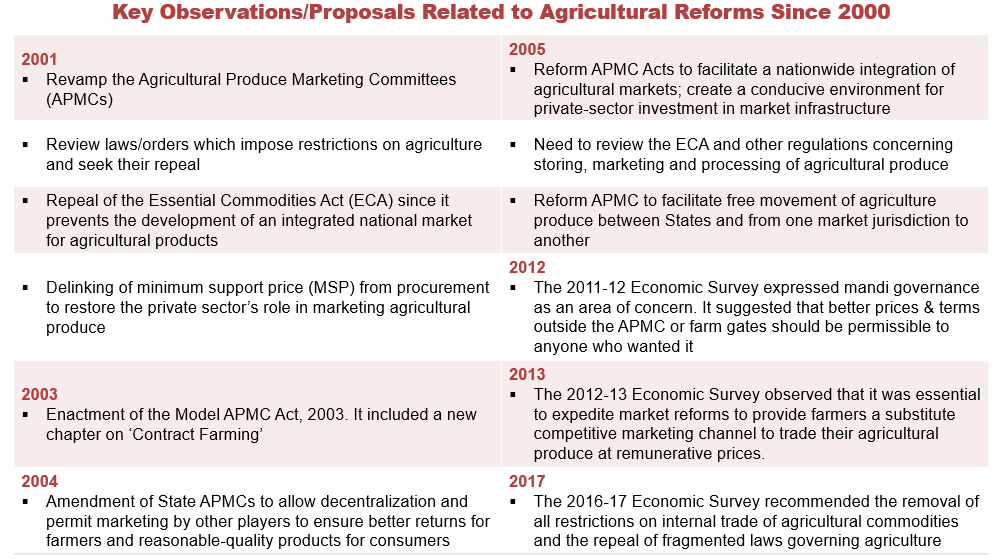

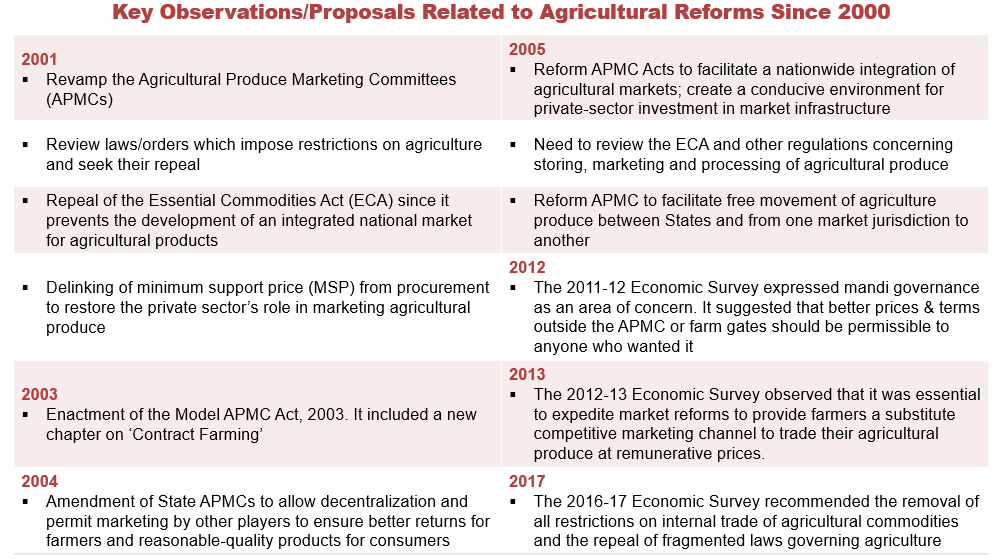

Since then, several developments have taken place which finally culminated in three agricultural reform bills that were recently enacted into law by both houses of Parliament and have also received the President’s assent. During these two decades, various committees, task forces and commissions recorded their observations and put forth several proposals, some of which are highlighted below:

Even a cursory reading of the above will indicate that over the years, observations and proposals have mainly focused on:

- reforms to the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs)

- repeal/review of the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) and other laws that have outlived their utility, and

- removal of restrictions to enable the free movement of agricultural commodities across the country

Regulatory reforms pose a complex problem in a country where over 40% of the population, predominantly in rural areas, is engaged in agriculture. What compounds the problem is that agriculture is a State subject, and agricultural markets have so far been regulated by state-specific laws under the APMCs.

Erstwhile regulations under the APMCs mandated that sale/purchase of notified agricultural commodities could take place only through mandis or wholesale markets regulated by the Government. Both traders and intermediaries (middlemen) needed a license to operate. In many States, mandi-specific licenses were issued by the APMCs. The overriding intent of these and other regulations was the protection of farmers’ interests; in reality, however, it left farmers at the mercy of intermediaries for funds, information and other services. Over time, these vested interests – who also enjoyed considerable political patronage – became power-brokers and took over the functioning of mandis.

In the last few decades, various Central Governments have struggled to reform the farm sector due to States’ dominant powers as well as the intermediary-politician nexus. Attempts were made to bring a unified structure to agricultural markets in the form of the Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2017 and the electronic National Agricultural Market (e-NAM). While these measures led to some degree of progress, the rate of change was deemed fairly slow and the actions differed widely across States to make a noticeable difference.

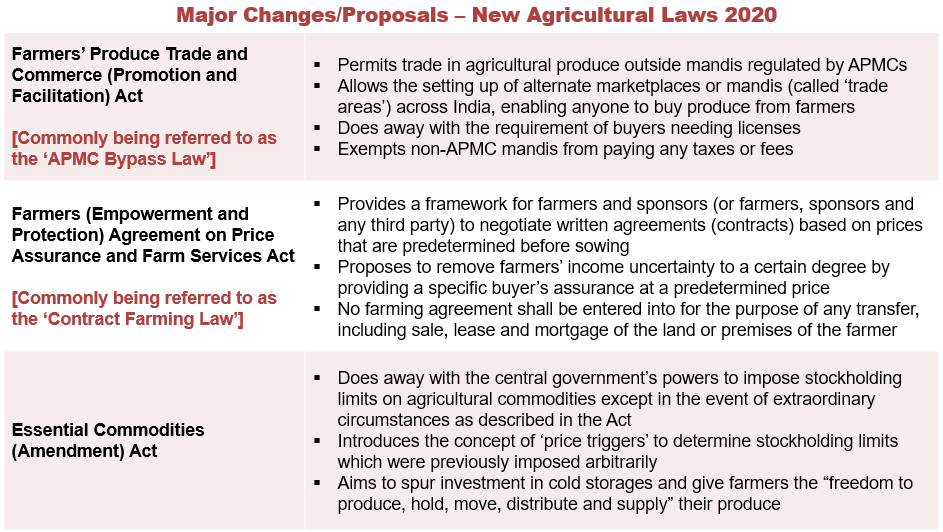

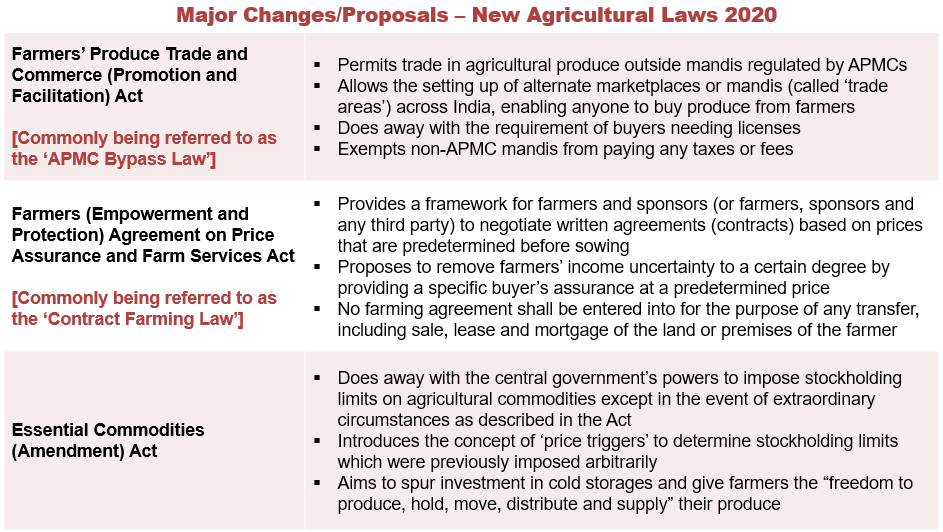

With the enactment of three new laws in 2020, the Central Government has signalled its intent to bring about wide-ranging and much-needed reforms to India’s agricultural market. Major changes proposed by these laws are summarized below:

Read together, the underlying intent of the three laws – as is being reiterated by the Government and supporters of the laws – is to free farmers from their dependency on intermediaries and give them the freedom to sell their produce anywhere in India. Protesting farmers and those opposed to the new laws, on the other hand, assert that ground realities are vastly different.

In India, an overwhelming majority of farm holdings are extremely small, with average farm size being 1.08 hectares as per a 2018 survey. Due to limited farm sizes and the perishable nature of their produce, farmers are compelled to sell their crops immediately after harvest so that they can prepare for the next sowing season, repay their debts, and avoid practical issues such as lack of storage and transportation facilities. Farmers contend that under such circumstances, do the new laws really present them with an opportunity to sell their produce anywhere in India?

Among the most contentious issues is that of a minimum support price (MSP) for 23 crops – the previous practice was the Government notified the MSP before the start of the Rabi and Kharif cropping seasons every year. Farmers are concerned that with the enactment of the new laws, they will not have recourse to MSPs for their produce. It is widely accepted that MSPs act as a safety net by protecting farmers from price fluctuations due to market conditions or natural calamities. Looking at it objectively, there appears to be a high degree of ambiguity regarding the enforcement of MSPs under the new regulatory framework.

While the Government’s resolve to introduce greater transparency and flexibility in agricultural markets is laudable, it must also pay heed to farmers’ genuine concerns. More importantly, it is the responsibility of the Government to remove ambiguities in the new laws, particularly with regard to key issues such as MSPs.

For any law to be effective, it must be free from ambiguities and lay down provisions clearly. There are many missing pieces in the three farm laws which are being hailed as a “watershed event” for Indian agriculture. Primary among these are issues related to the withdrawal of MSPs and mandis regulated by APMCs. The APMCs were established in the 1960s, and while their functioning leaves much to be desired, the fact is that farmers will find it difficult adapting to the new agricultural market infrastructure overnight. Written assurances from the Government will go a long way in allaying their fears.

The three laws need to address other key concerns explicitly, including:

- regulation and regulatory oversight for the new (non-APMC regulated) trade areas and for any upcoming electronic platforms

- dispute resolution mechanism of transactions which take place outside APMC mandis

- preventing the formation of intermediary cartels in non-APMC mandis

- protecting the interest of farmers from large private players and corporates – there are apprehensions that the latter will use their bargaining power to influence prices and leave farmers, especially small farmers, worse-off than before

If the new laws are indeed seeking to revolutionize and modernize agricultural markets, they must leave no scope for any misinterpretation or confusion which will place one party (in this case farmers) in a disadvantageous position. It should not be that structural deficiencies of one system are replaced by similar deficiencies in another – this will be akin to serving old wine in a new bottle. Both the Government and opposition parties need to stop politicizing the issue and give farmers an opportunity to be heard. All valid concerns should be addressed, and the farm laws should be suitably amended to ensure that all ambiguities and doubts are put to rest. Only then can it be confidently said that the country has sown the seeds for a second green revolution.

The author is a Partner at Dua Associates